29 March 2019. I am in Morocco, on the jury of the Tetuan Film Festival, one of those days when we watch three films back to back. We were sitting in the cinema to watch the second film of the day. When I picked up my phone to switch it off, I received a text from Türkiye: ‘We lost Ayhan Ergürsel, my condolences’. I excused myself from my fellow jury members and walked out of the cinema. I sat in a coffeehouse until I got over the initial shock. One glass of tea, two, three...

Ayhan loved tea. He brewed the best tea. He usually slept in during the editing stage. When I’d arrive in the office in the morning, as soon as I opened the door, he would say ‘Pelin! I had a great idea last night,’ and he would serve us tea. It's not always possible to see a member of the crew embrace the film as much as the director and is as excited, and Ayhan was one of the first to make me feel that. It is a very precious feeling that I will never forget.

The coffeehouse keeper in Tetuan asked if I wanted another cup of tea. I said no. A strong smell of hookah filled the place. I don't know if Ayhan smoked hookah, but he loved cigarettes. His mind never stopped during our smoke breaks, he would continue editing on the balcony.

I left the coffeehouse. I started walking, I walked in some narrow Tetuan alleys ––dead ends. I came across old men in colourful hooded robes. Ayhan would have burst out laughing if he saw them... If he had heard the birds in Morocco, he would immediately start imitating them. Ayhan knew birds very well. He would whistle the chirp of the bird we found to be most suitable for the scene, and then the sound designer would have to search for it!

Moroccan boys are very keen on football like back home. I stumbled upon a match on every street. Ayhan wasn't much interested in football, but he loved children. And children loved him ––those with strong intuition immediately distinguish each other. It was while watching Ayhan at the editing table that I realised that editing was more about intuition than maths. After a while, we were snapping our fingers at the same time at the moment of cutting the plan. We got on. Not always, of course.

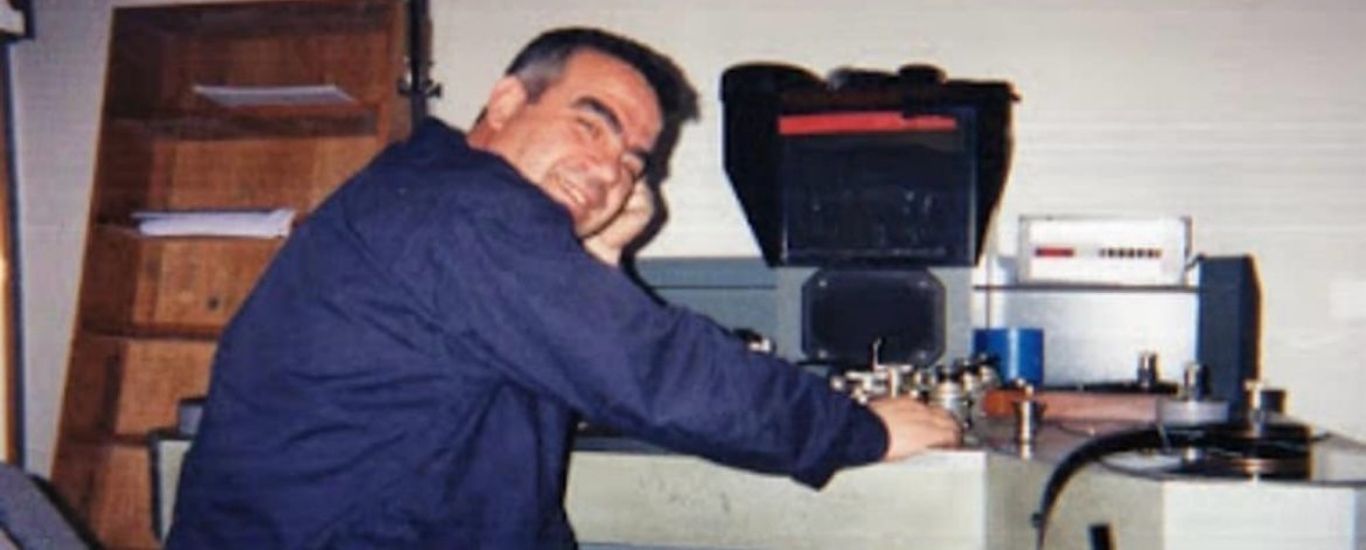

In 10 to 11, he wasn't on good terms with the computer, in fact he never sat at the computer, usually our assistant editor and I did, sometimes. But you had to see him at the 35mm editing table. I first met Ayhan at that table, in 1997, at Yavuz Özkan's Z1 Film Workshop. We used to do montage exercises with the discarded parts of Mr. Yavuz's film Anatomy of a Woman, under Ayhan's supervision. We were mesmerised by his speed at that table and the way he connected the plans without leaving any stitch marks. By the time we got to edit The Watchtower, we were sharing the steering wheel; sometimes he would sit at the computer, sometimes I would. When we couldn't agree on a scene, he would say, ‘Just a minute, just a minute!’, he would sit in the chair, edit in two minutes what he had just verbalised, and then say, ‘There!’. His exclamation ‘There!’ would make us both laugh. Then we would move on to a completely different alternative. Never tiring, never getting tired.

I learnt so much from Ayhan. I can't imagine Ayhan doing anything else, his excitement never waned. He never came to the set. Neither he wanted to, nor I did. He would spare himself from the goings-on on the set, keep his mind clear and ready for the editing. During the shooting, he would watch the dailies we would send him, and he would comfort me with a phone call occasionally: ‘There are no gaps, nothing’s missing, just relax, take it easy.’ After the shooting was wrapped, I always got impatient and wanted to start editing without taking too long a break. As such, you carry the set and the events that happened there to the editing room for a while. It would take me 3-4 weeks to completely grow apart from the set and set a distance. Neither he would ask about the set, nor I would tell him anything about it. We would never look back at the script. We would start working as if nothing had happened, as if we were starting a new film. We wouldn't come to a full stop until we were both satisfied. Ayhan was very patient.

One of his nicknames was ‘One-frame’. He was with us also when we were mixing 10 to 11 in Germany. While the mixer was trying to find out how many frames the synchronisation had slipped, you would hear Ayhan's voice: ‘one frame to the left’. Although the mixer would be slightly upset, he couldn't hide his admiration. Ayhan would immerse himself in his work so much with his intuition, his emotions, his mischievous, brilliant mind that once he entered that world, he wouldn't exit until the film was completed. He loved his work and he loved cinema. We used to talk for a long time about films and film-like lives. Even if he was offended, he would not be resentful.

He was never anything but himself, nor did he try to be. Ayhan is one of those individuals whose absence will always be felt ––both as a person and as an editor.

Evening fell in Tetuan. Ayhan didn't like the streets when it got dark. People, chickens, roosters... Ayhan didn't like crowded places either. So, I immediately left the market and continued walking along a lighted street.

–Pelin Esmer