Words: Kutlukhan Kutlu

Images courtesy of Park Circus/Universal

A child, breathlessly absorbed by a film, and yet starting to understand that the exhilarating images she is watching is but the construction of a ‘director’… A cinephile who passionately loves not only to watch films but to reflect deeply upon and discuss them, who, in parallel with his own life’s audio track, has opened up another one, rooted to the history of cinema’s great dialogue… An experienced filmmaker who faces arduous problems and scratches his head in search of inspiration from within the same great dialogue…

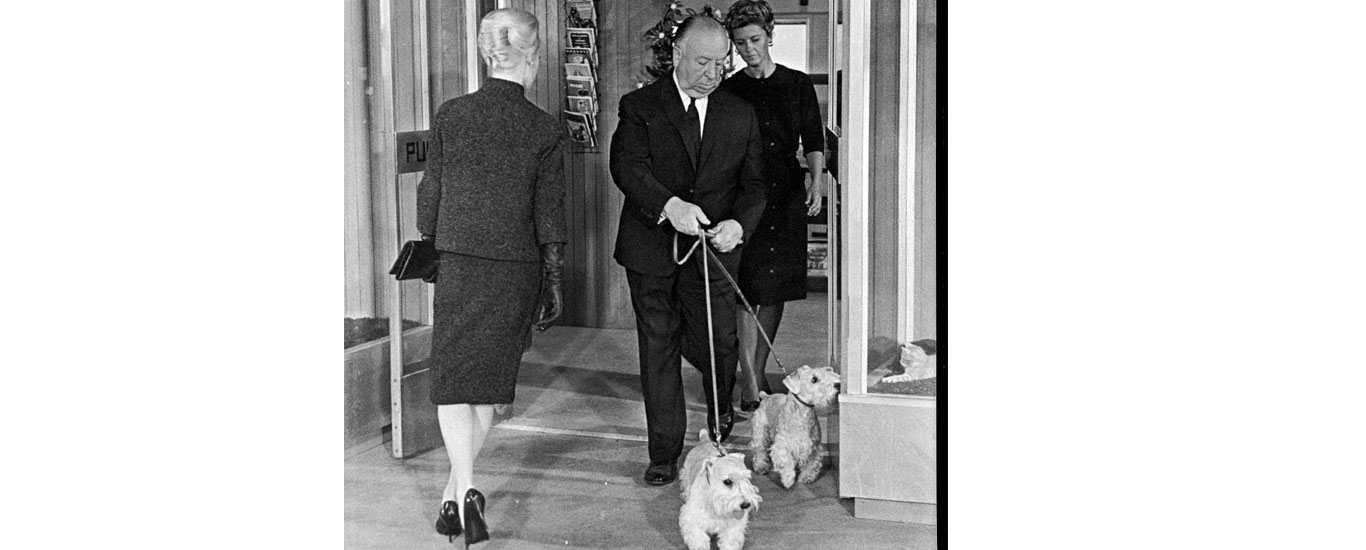

‘What is it that binds these three together?’ If the answer to this question were a single director’s name, it would probably that of Alfred Hitchcock’s—the storyteller, the master of the art of holding cinema’s excitement, creativity and craftsmanship in a magical bowl and make lightning strike miracle inside it.

Alfred Hitchcock’s preciousness doesn’t only consist in his ability to bridge the different facets of our relation to and love for cinema, but also in how he has blessed us with a very rich oeuvre in the process: from his UK years spreading along the 1920s and the 30s, to his years of maturity during which he became one of Hollywood’s most important directors and worked with the biggest stars of the era, his filmography is a magnificent treasure, comprising different gems in each period. Stanley Kubrick, whose films were screened last year as part of the Festival’s ‘Masterpiece Factory’, was known for his determination to shoot ‘few but essential’ films, staying away from the industry and talking very little about his work. Alfred Hitchcock, on the other hand, not only made more than 50 films, but also played an important role in asserting the notion of ‘director as the author’ by creating almost a character of himself in front of the camera, never hesitating to speak in length about his work. So much so that part of his legacy extends beyond his films, to a television series which he presented in person, helping the public become closely accustomed to his face in the process, and one of the most important conversations in the history of film publishing.

Well, the child in front of the screen also anticipated: ‘When is Hitchcock going to appear?’. He would spot the familiar silhouette missing the bus, winding up the lyricist’s clock through the opposite window, walking from the hotel lobby to the corridor, sitting by Cary Grant in the bus, and even, if he looked attentively enough, in the newspaper slimming diet ad in Lifeboat. Maybe he had become familiar with his voice, movements and expressions from running across his TV film series Alfred Hitchcock Presents on television. Thanks to such an acquaintance, the same child would start to grasp the fact that someone was responsible for all this witchcraft called cinema, that all this was being devised in that person’s mind.

Yet, interestingly enough, despite having gained a status in England as one of the country’s most talented film craftsmen with such films as The Lodger, Blackmail and 39 Steps, he wasn’t recognized there as a true artist for a long time. Yes, when he came to America, Hitchcock played an important role in the transformation in Hollywood from a system that placed the producer and even the actors above the director to one that recognises the latter’s pivotal role in giving the film its distinctive character… But in order to truly assert the director’s monumental position as we grant it today by fully displaying their own cinematographic world, expression form, thematic preferences, obsessions and favourite motifs, a need would arise for someone whose first step would be revolutionary film criticism before evolving into a revolutionary film director: the Cahiers du Cinéma writer who coined the term ‘auteur’ and New Wave director François Truffaut.

Truffaut’s meeting in 1962 with Hitchcock, who was then in the midst of Birds’ post-production, emerged as one of the biggest classics of cinematographic literature. Published in 1966, ‘Hitchcock/Truffaut’ showed the entire world that the ‘master of suspense’ also mastered the art of reflecting on cinema as much as crafting it, forming sentences with projected images. Not to mention that it constituted a treasure mine for all those who have felt the strange appeal and unavoidable difficulties of translating an art comprising of images into words.

The master’s trademark and influence as the man behind the camera finds maybe its purest expression in this question:

‘What would Hitchcock do?’

According to his daughter Laura, Truffaut asked himself this question quite a lot. Later on, Steven Spielberg, who would mention Truffaut in his Close Encounters of the Third Kind, would ask himself the same question as well, while looking for solutions on set, resting on a mechanical shark prop that not only failed to look scary but also sunk whenever placed in the water. At that precise moment, Hitchcock’s cinema represented for him the true mastery of suspense as well as a deep well of inspiration in terms of general cinematic narration.

Let us remember his famous phrase: ‘Some films are slices of real life. Mine are slices of cake.’ He also said: ‘I’m never satisfied with the ordinary. I can’t do well with the ordinary.’ Long before Spielberg or James Cameron, he compared his role as a director to that of a ‘roller-coaster operator.’ His main goal was to keep the viewer in the palm of his hand. But as the filmlover and filmmaker watch his films again and again, they discover a fascinating truth: the afore-mentioned cake is not the narrated but rather the narration itself.

Though delving in and out of many genres throughout his career, it is not the stories he chose which define Hitchcock’s cinema, but rather the way he told them, how he weaves the film from moment to moment, how he utilises angles, sounds, music, and the ‘image size’ as he himself put it, and how he creates a rhythm, rimes, contrasts and eventually emotions with the help of all these tools. Besides, even though the world’s most talented directors very often turn to the old master for inspiration, these achievements are not as easily exactly reproducible as they may seem: when Gus Van Sant attempted at one of the most interesting experiments in the history of cinema (the exact, shot by shot reproduction of Psycho, only in colour), the result oddly missed the effect the original had achieved... Hitchcock’s proverbial preparedness and constant attention to filmic mathematics, from the faces and colours to the most minute, sometimes almost invisible details, obviously had a huge impact on his films’ general texture and outcome. Whether the story be a breathless espionage as in North by Northwest, which was the precursor of the James Bond series, or a strange, oneiric, psychologic thriller as in Vertigo, or a structural essay, making life resemble a cinema set as in Rear Window, Hitchcock’s decisions regarding audio-visual narration have always enabled him to create both highly detailed and personal realms.

During their conversation, when Truffaut asked him: ‘Are you in favour of the teaching of film in universities?’ the master replied: ‘Only on condition that they teach cinema since the era of Méliès and that the students learn how to make silent films.’ Because through his insistence on ‘pure cinema’, he primarily meant the seminal methods of silent movies. He may have shot a number of films where dialogue is predominant, some even structurally close to theatre, yet he considered no less that cinema’s purest form is when what is happening on screen is easily comprehensible without dialogue. After studying engineering, Hitchcock started his film career designing title cards for silent movies. He drew inspiration from the German expressionists in order to both attain this silent language and manage to inspire strong emotions in his viewers.

As to the tool which constitutes the basis of cinematographic language, he identified it as editing. Ever since Lev Kuleshov’s experiment almost one century ago showing how emotion passed on during the succession of two images, how we are influenced by the previous image in a sequence, this technique has constituted the basis of cinematographic grammar. Hitchcock himself carried out a sort of variation of Kuleshov’s famous experiment. He described the tool as bearing the potency to ‘either contract time or extend it,’ and considered this to be the very throbbing of cinema’s heart.

Hitchcock considered that what he had fundamentally achieved in Rear Window was a return to the ‘essence’ which Kuleshov had underpinned. Here is his own account of what he had aimed at: ‘You have an immobilized man looking out. That’s one part of the film. The second part shows what he sees and the third shows how he reacts. This is actually the purest expression of a cinematic idea.’ But beyond this basic level, no later than the film’s very opening, when Hitchcock introduces us to the setting where the whole story will take place –the courtyard surrounded by windows which are openings on as many individual lives– he also sets the rules of another game: by fixing the camera to the character, us to the camera and therefore to the character’s position, he places the character in the position of the ‘voyeur.’ In other words, these ‘slices of life,’ which could be considered as relatively common within the film’s own frame, bear a brand new meaning and emotion when seen through a second frame, that of the window frame, putting us in the position of the voyeur as well. In that case, did Hitchcock consider voyeurism to be, as much as cuts, the purest, simplest expression of cinema? While accompanying James Stewart as he watches from behind his window, sometimes with his naked eyes, sometimes with binoculars, sometimes through a telephoto lens, one wonders whether cinema and the ‘sharing of guilty pleasures’ are not regarded as the same thing to some extent somewhere in Hitchcock’s brain.

Fear is one of these guilty pleasures of course. Hitchcock himself confessed to being agitated by many fears, which he sometimes linked to his parents terrifying him as a child, or to his Jesuit upbringing. And he loved creating tension within the movie theatre, letting the viewer, nailed to their chair just like James Stewart in Rear Window, lean back a little before startling with shock and fear, almost as though he was looking for people to share his fears with. In order to achieve that, he didn’t hesitate to break the rules sometimes. In Psycho, the apparent star, Janet Leigh, is eliminated one third into of the film, and we are left alone with the killer for the rest. The rendition of this crucial shift in a scene so complex that only someone as attentive to details as him could undertake shows how much innovation, preparation, and thoroughness the game he plays with the viewer demands. As a matter of fact, Hitchcock attributed his own urge for preparedness precisely to his fears, to his unwillingness to be confronted with unexpected situations.

Since mentioning Janet Leigh… Hitchcock managed to obtain fantastic results from his actors, even when he considered them to be just another cinematic tool in the hands of the director, who he believed was the true owner and teller of the film. He described Montgomery Clift’s proposition of something contradicting for his character as an interference in the director’s space, yet he granted such prominent actors and actresses such as Ingrid Bergman, Cary Grant, James Stewart, or Grace Kelly some of their most memorable performances. After all, the stars were but shining parts among the natural elements of his cinema, representing a ‘slice of cake’, and things ‘bigger than life’.

‘I believe my name has become known to motion picture audiences throughout the world as a trade-mark for the startling, out-of-the-ordinary psychological suspense mystery films,’ said Hitchcock, while defending his comprehension of the director as the film’s owner, in the Hitchcock Manifesto. But for us, he represents a lot more than just this. After all, the impression he has left is not circumscribed ‘only’ to masterpieces whose cinematographic power is intact and ever rediscovered by film enthusiasts. His cinema has influenced countless directors, from Spielberg to Scorsese, from David Fincher to Park Chan-wook. Among his ‘imitators’, one can count such masters as Argento and De Palma. Korean director Bong Joon-ho, this year’s Oscar-winner with Parasite, considers him a personal source of inspiration. In a nutshell, he has become a cinematographic fountain, a beacon of inspiration.

Ultimately, the question ‘What would Hitchcock do?’ has long crossed the axis line and passed through to the other side of the screen, all the way to the afore-mentioned little child’s for instance… Let’s not forget that here, in this country, a group of film critics –each accomplished cinephiles to be expected– united to publish a magazine, without any financial expectations, that was called ‘Arka Pencere / Rear Window’… Moreover, the magazine’s main sections were all named after films by the ‘master’. This, if only, is wonderful proof of how Hitchcock’s cinema operates as a cultural binder, of its historical meaning for cinema lovers and of the liveliness of his sombre, mischievous definition of cinema.