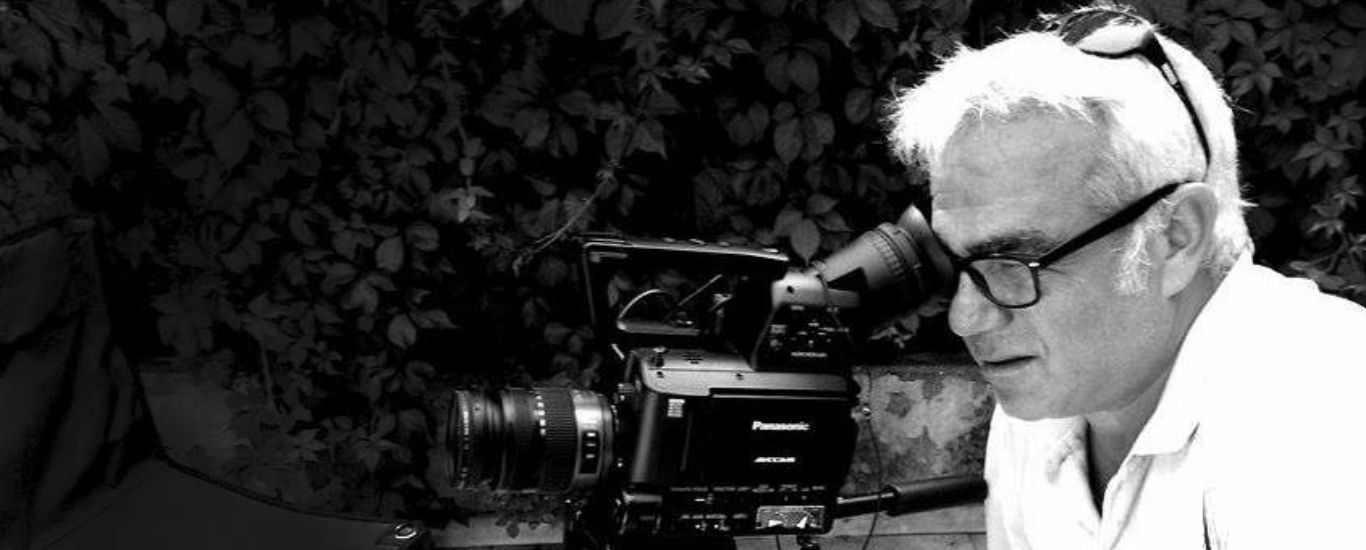

I met Ayhan Ergürsel in 2004 during the editing of my second film Meleğin Düşüşü / Angel's Fall, which I also produced. Hande Güneri Ağdaş and I had finished the rough cut of the film and were looking for a professional editor for the fine edit. Ayhan had edited Nuri Bilge Ceylan's films such as Koza / Cocoon, Kasaba / The Town, Mayıs Sıkıntısı / Clouds of May, and Uzak / Distant.

When we decided to work together for Angel's Fall, I naturally thought that Ayhan would read the script of the film before we picked up the scissors. Ayhan said that he wasn't interested in the script at first (he wasn't going to be interested later on either), but after watching the rough cut, he wanted to watch all the sequences of the film ––including the erroneous shots. And he watched all the footage, which lasted more than fourteen hours in total.

From time to time he would take notes, from time to time he would get bored and go out on the street with a cup of tea in his hand, take a few laps around Teşvikiye and return to the desk. Hande helped him because he didn't know how to use the computer and the programme we used for editing. Ayhan had his own technical language and it took a long time for him and Hande, who used the computer programme, to establish a mutual language.

If you'd ask me who is a passionate filmmaker, I would say it is someone who never tires of watching the scenes he has shot over and over again and who constructs permutations with them. During the editing phase of Angel's Fall, Ayhan would stop the frame, re-watch all the shots over and over again, wandering through the dark alleys of a film whose story he had not yet mastered (because he had not read the script), juxtaposing unrelated frames and taking notes in a quite illegible handwriting.

We would witness him enthusiastically come to the office every morning with a new idea and new notes.

These notes and ideas were like Ayhan's efforts to make sense of certain situations and emotions that we experienced in life that we could not quite place within a framework of causality. It was as if he was interpreting a dream or trying to see the whole picture by looking at a single piece of a puzzle with thousands of pieces.

His extremely complex yet as creative effort was to fathom and unearth the story that silently flowed beneath a chaos of script, actors, light, sound, dialogue, and fragments of space and time. In doing so, he adhered to the basic emotion of the film in order not to lose his way, and removed and discarded anything that obstructed the flow of that emotion between sequences and scenes. He even did not hesitate to use some of the sequences that I did not think of using due to an incorrect camera movement or an actor's action that I judged wrong, for his "own edit."

This was the opposite of a conception defined as mainstream or commercial cinema expects from an editor. A unique approach that can only be of an artist who resists the pressure of the story, the message, the script, the star, the director, and the producer, and in doing so, has no other concern than revealing the pearls concealed by the mass of material at hand...

The moments we enjoyed the most when working with Ayhan were when we discussed the Foleys of scenes. We would extract sounds from the CDs we bought at the flea market, which contained various sound effects, and tried some of them on the film. We would see by experimenting that sound was an indispensable element of creative editing and that at some moments sound, rather than image, created an effective auditory atmosphere, and thus we would succeed in cleansing our film of its artificial excesses. This was also important in terms of knowing what we wanted from the sound designer before sending the film their way. Editing is a process stage where sounds are edited as well as images.

Today, I understand more clearly that Ayhan was not editing a film, he was discovering the ‘film’ within the film with a naive instinct. He would sometimes take dead ends, or make radical moves that would upend the chronology of the plot, or sometimes he would present us with bizarre scenes that had us roaring in laughter. Could it be that his lack of formal film education, his background as he grew up, his humour, his illiteracy, and even the fact that he did not watch many films other than the ones he worked with are factors in his risk-all, free-acting, daring attitude?

After Angel's Fall, we worked with him on Egg, Honey, and Wheat. We spent many months together in almost every aspect of these films, which were all shot on 35mm film, from their laboratory processes to the editing and sound design. I would send Ayhan the dailies from Tire, Çamlıhemşin, Detroit or Cologne where the shoot was; he would watch the fresh sequences and send me notes from afar.

He was a man of great foresight. When we completed editing, he would often make accurate predictions regarding the fate of the film ––such as the festivals it would go to, the awards, or the number of viewers.

Ayhan lived his life just like his notion of editing. His mind combined many unrelated situations that he experienced, and in life he travelled on a fine line between imagination and reality. His legacy comprises numerous unforgettable beauties from a life full of challenges and sometimes harsh solitude.

I remember my big-hearted, wonderful friend at every film shoot, at every editing table where Hande and I sit together, and I am grateful for the work he put into my films and for witnessing each other's lives, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank Ayhan Ergürsel once again.

May his soul rest in peace and may he be granted a place in heaven.

–Semih Kaplanoğlu